What is a SPAC?

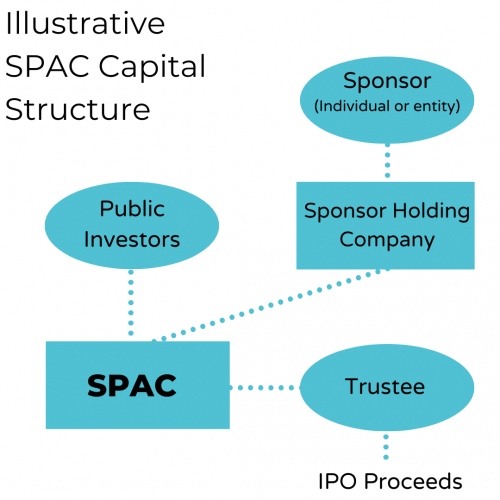

A Special Purpose Acquisition Company (“SPAC”) is a newly formed entity that uses IPO proceeds to fund a private operating company’s acquisition. The SPAC itself is merely a legal entity – it has no employees, no operations, or assets. A SPAC is also known as a “blank-check” company.

The proceeds raised in an IPO go into a trust account. The SPAC management team (also known as its sponsors) then acquires an existing operating company. If the SPAC sponsors cannot complete the acquisition in the allotted timeframe (usually 18 months with a possible extension of 6 months), the proceeds held in its trust are returned to the investors.

Where Did SPACs Come From?

SPACs were initially formed in 1993 by a creative investment banker named David Nussbaum. “It’s taken me 27 years to become an overnight sensation,” Nussbaum says.

SPACs have been around for decades. They have been used as alternative investment vehicles and an option of later-stage funding for companies looking to go public. Since the 1990s, the popularity of SPACs has ebbed and flowed depending on economic conditions, trends in the capital markets, and the overall health of the IPO market. The problem with SPACs in previous decades is that their use was mainly limited to pump-and-dump schemes.

Where Are SPACs Going?

Regulations have changed since then, and in 2020, several trends converged to drive the popularity of SPACs and lend them an air of legitimacy.

- In early 2020 there was an abundance of un-invested capital sitting around. The amount of “dry powder” held by private equity was estimated to be near $1.45 trillion as of June 2020.

- SPACs grew in popularity as an attempt to mitigate the increased market volatility caused by the global pandemic.

- The entrance of several high-profile investors and hedge fund managers has lent credibility to the structure as a reputable investment vehicle.

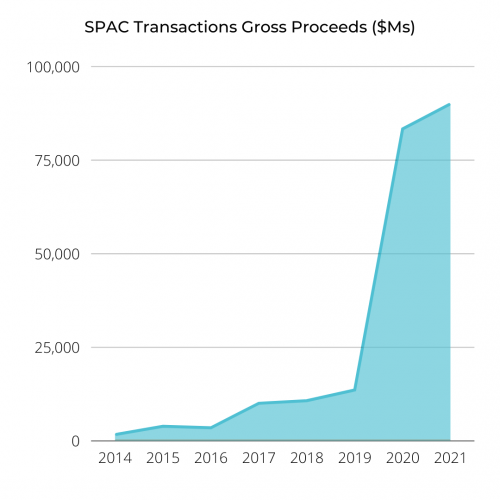

All in all, SPACs raised more in 2020 than the previous ten years combined1. Between January and October of 2020, 165 SPACs were listed2.

SPACs are already proving to be one of the hottest investing trends in 2021, surpassing the blowout year of 2020.

Who Is Getting Rich Off SPACs?

SPACs have been enormously profitable for their sponsors. Typically, 80% of the money goes to the public company, while 20% goes to the SPAC sponsors to compensate them for setting it up. Some investors are concerned about the sponsors’ commitment and are pushing to have “promotes” (the sponsor’s stake in the firm) more directly tied to the company’s performance post-merger.

Chamath Palihapitiya, one of the most prominent investors in the world of SPACs, recently faced backlash. Regulatory filings showed that Palihapitiya sold his entire stake in Virgin Galactic, a company he took public via SPAC. The move raises concerns about how well other investors understand the risks associated with these investments.

SPACs can also be structured to favor sponsors over later investors. There are efforts underway to make them more friendly to all shareholders.

SPACs can be profitable for later investors as well. The average share price of companies that went public via SPAC over the last two years is around $18 per share, nearly double the starting $10 price.

Are SPACs Here To Stay?

Many executives view speed as one of the most substantial benefits of the SPAC route, with some mergers completed in as little as three months. With a traditional IPO, management has to stay quiet about taking the company public. Retail investors are not allowed to know. The same restrictions do not apply to SPACs. The drawback is that SPACs are often more complex transactions than IPOs and the accounting is typically more complicated.

Not everyone is a fan of SPACs. For instance, Charlie Munger said on the topic, “The world would be better off without them.” Mr. Munger sees SPACs as yet another form of irresponsible gambling, adding, “This kind of crazy speculation in enterprises not even found or picked out yet is a sign of an irritating bubble.”

What do you think? Are SPACs an irritating bubble or the future of financing for public companies?